De la pénurie d'essence à Lawrence d'Arabie (+ebook et film stream)

C'est désormais toutes les semaines que le Blog Culture-Universelle sera nourrit, en effet trop de travail sur d'autres médias ;-)

Pour aujourd'hui, tout d'abord, c'est le Citoyen Marcel qui va ouvrir le sujet, comme d'habitude...

Nous sommes face à la pénurie de pétrole... les voitures à pédales vont faire leur retour, les vélos taxi aussi, et bientôt c'est en pousse-pousse que les touristes iront visiter les monuments de notre capitale, en espérant bien sûr qu'un imbécile mahométan ne se fasse pas cramer sur leur passage ;-)

Et donc, je pensais à pétrole, donc à la péninsule arabique... et de fil en aiguille... à l'illustre britannique : Thomas Edward Lawrence... alias :

Lawrence d'Arabie

Tout d'abord, pour les francophones, un documentaire très intéressant sur T.E.Lawrence, sa vraie vie véritable... 1h50 de documentation.

And now, english speaking (enfin bref, pour ceux qui parlent et surtout lisent cette langue), vous pouvez télécharger... you can downloading...

The seven pillards of wisdom, pdf ebook with this link...

Les sept piliers de la sagesse, en format ebook pdf en suivant ce lien...

J'ai aussi trouvé l'article du 19 mai 1935 dans The Guardian (quotidien britannique) relatant le décès du héros:

May 19, 1935 - the death of Lawrence of Arabia

Strategist of the Desert Dies in Military Hospital

Lord Allenby's tribute - "Valued comrade"

We regret to announce the death of Mr. T. E. Shaw ("Lawrence of Arabia"), which occurred shortly after eight o'clock yesterday morning in Wool Military Hospital, Bovington Camp, Dorset. Mr. Shaw, who until recently was an aircraftman in the Royal Air Force, was injured in a motor-cycling accident on Monday night and did not recover consciousness.

Tragic as it is that such a remarkable career should have been ended by a simple road accident, an official statement issued yesterday shows that if his fight for life had succeeded it would still have been a tragedy, for Mr. Shaw's brain was irreparably damaged.

Mr. Shaw was 46 years of age.

After a post-mortem examination by Mr. H.W.B. Cairns, the London specialist, the following statement was issued: -

"The post-mortem examination conducted by Mr. Cairns showed such severe lacerations and damage to the brain that in the event of his recovery he would have only regained partial use of his speech and eyesight. In view of the immense activity and energy of Mr. Shaw it is felt that this may be some consolation to those who had entertained anxious hopes of his recovery."

Another statement issued was: "The funeral of Mr. T. E. Shaw, formerly Colonel Lawrence, will take place at Moreton Church, Dorset, at 2.30pm on Tuesday. The service will be a simple one and no mourning and no flowers are requested. Apart from those specially invited the service will be confined to his particular friends and those who were associated with him in Arabia.

It is understood that there will be no military escort.

When it was realised that the crisis had been reached, Sir E. Farquhar Buzzard, physician-in-ordinary to the King, Mr H.W.B. Cairns, the brain specialist of the London Hospital, and Dr. Hope Gosse, the London lung specialist, were called to the hospital.

Last night's broadcasts

Tributes to "Lawrence of Arabia" were broadcast from London last night by Field Marshal Lord Allenby and Sir Herbert Baker. Lord Allenby said that in Aircraftman Shaw he had lost a good friend and a valued comrade.

After recalling that they were closely associated in the campaign which opened in 1917-18 in Palestine and Syria, Lord Allenby said: "His co-operation was marked by the utmost loyalty and I never had anything but praise for his work, which, indeed, was invaluable throughout the campaign. He was the mainspring of the Arab movement and knew their language, their manners and their mentality. He shared with the Arabs their hardships and dangers. Among these desert raiders there was none who would not have willingly died for his chief. In fact not a few lost their lives in devotion to him and in defence of his person.

"He was a shy and retiring scholar, archaeologist, and philosopher swept by the tide of war in to a position undreamt of. He had a genius for leadership. Above all men he had no regard for ambition, but did his duty as he saw it."

Lord Allenby added: "He has left to us who knew and admired him a beloved memory and to all his countrymen an example of a life well spent in service."

Sir Herbert Baker was unable to be at the microphone and his tribute was read for him. He first met Colonel Lawrence in Oxford shortly after the war and was fascinated by him. "He seemed to radiate a magnetic influence," said Sir Herbert. "When he last stayed with me about a month ago he pleased us by eating two human meals a day and expressing an ardour to do some great national work."

Other tributes - Mr Winston Churchill:

In Colonel Lawrence we have lost one of the greatest beings of our time. I had the honour of his friendship. I knew him well. I hoped to see him quit his retirement and take a commanding part in facing the dangers which now threaten this country. No such blow has befallen the Empire for many years as his untimely death. The personal sorrow which all he knew him will feel is deepened by the national impoverishment.

Voici aussi un article du magazine Time du 28 novembre 1932 au sujet du livre d'Homère: "L'odyssée", traduit par Lawrence sous le pseudonyme de T.E.Shaw.

Books: Scholar-Warrior

Monday, Nov. 28, 1932

THE ODYSSEY OF HOMER—Translated by T. E. Shaw —Oxford University Press ($3.50).

His family name was Lawrence; to Arab warriors he was Aurans, Emir Dinamit, ''the World's Imp"; newspaper Warwicks dubbed him "the uncrowned King of Arabia"; some of his immediate superiors in the British Army called him every epithet in the calendar; now he answers only to his legally changed name of "Shaw." An archeologist of the first rank, he is now a mechanic and "the associate of menials"; once a colonel, he is now, by choice, a private; with a reputation that could still be cashed in for much fine gold, he is content with his army pittance of 60¢ a day. This Royal Air Force mechanic, Aircraftsman Thomas Edward Shaw, known to the world as Col. T. E. Lawrence of Arabia, whose most intellectual duty at present is "tinkering with engines," has just finished a four-year spare-time job of translating The Odyssey into English prose.

The Book. "The twenty-eighth English rendering of the Odyssey," says modest Translator Shaw, "can hardly be a literary event." Some of his 27 predecessors: George Chapman (1614), Alexander Pope (1726), William Cowper (1791), William Cullen Bryant (1871), William Morris (1887), George Herbert Palmer (1891). Samuel Butler (1900), S. H. Butcher & Andrew Lang (1898), A. T. Murray (1919). Scholastically, Shaw's translation ("made from the Oxford text, uncritically") may not please Homeric scholiasts. "I have not pored over contested readings, variants, or spurious lines. . . . Wherever choice offered between a poor and a rich word richness had it, to raise the color." Literarily, Shaw's faint praise of "the first novel of Europe," his strictures on its author, may damn him in the eyes of the orthodox. Shaw's inverted English modesty, which will not let him believe in heroes, which makes him deprecate the importance of anything he himself has been concerned with, is indicated on the title-page ("The Odyssey of Homer newly translated into English prose"). It may also be reflected in his always-belittling attitude toward a book the world has agreed to call great.

The Odyssey, he says, is "neat, close-knit, artful and various" but "never huge or terrible," never "great art. ... In this tale every big situation is burked and the writing is soft." Homer he calls "as muddled an antiquary as Walter Scott. . . . He thumb-nailed well" but his characterization was "thin and accidental." Though some modern scholars agree with him that The Odyssey is a much later work than The Iliad, most will think Shaw goes too far in saying "this Homer lived too long after the heroic age to feel assured and large." Penelope is "the sly cattish wife," Odysseus "that cold-blooded egotist," Telemachus "the priggish son who yet met his master-prig in Menelaus."

Typographically the book is a collector's item of masterly simplicity, printed under the direction of Bruce Rogers, No. 1 U. S. typographer.

The Story of The Odyssey, as every schoolboy used to know, is the tale of wily Odysseus' wanderings after the fall of Troy. Ten long years he and his comrades were buffeted about from disaster to disaster before hostile Poseidon, god of the sea, would let Odysseus return to his native island of Ithaca and his faithful wife Penelope who, besieged by unruly suitors, still hoped for his coming. Because they had killed and eaten the sacred oxen of the Sun, all his ship's men perished on the way. But Odysseus finally got there, straightened up his house, convinced his wife it was really he behind the wanderer's rags.

Of The Odyssey's purple passages one of the most famed describes Odysseus' meeting with his old dog Argos. Shaw's version: "As they talked a dog lying there lifted head and pricked his ears. This was Argos whom Odysseus had bred but never worked, because he left for Ilium too soon. On a time the young fellows used to take him out to course the wild goats, the deer, the hares: but now —he lay derelict and masterless on the dung-heap before the gates, on the deep bed of mule-droppings and cow-dung which collected there till the serfs of Odysseus had time to carry it off for manuring his broad acres. So lay Argos the hound, all shivering with dog-ticks. Yet the instant Odysseus approached, the beast knew him. He thumped his tail and drooped his ears forward, but lacked power to drag himself ever so little towards his master. However Odysseus saw him out of the corner of his eye and brushed away a tear. . . . He plunged into the house, going straight along the hall amidst the suitors; but Argos the dog went down into the blackness of death, that moment he saw Odysseus again after 20 years."

Translator Shaw may well have been reminded more than once of another war, when Arabs, counseled by a stranger as wily, energetic and heroic as Odysseus, fought against the Turks for an idea as beautiful to him as Helen; may well have remembered some of his banished names when he wrote Odysseus' words to the shade of Agamemnon: "What an army of us died for Helen."

The Translator. Archeologist by trade and inclination, Lawrence (he has not yet written a book signed "Shaw") originally intended to be only an archeological author. One of the books which he has never found time to write was to prove that the dating of ancient pottery in England is all wrong. Though a brilliant, omnivorous student with an enormous and accurate memory, though he won Oxford's highest scholastic honor (a fellowship at All Souls), scholars would not call him a scholar. He wrote two-thirds of Seven Pillars of Wisdom, his history of the Arab revolt, at odd moments during the Peace Conference at Paris; the introduction was written in an airplane flying from Paris to Cairo. At Reading railway station, the following December, the two-thirds-finished MS was stolen. He set to and rewrote the whole thing in three months— 34,000 words of it at one sitting, between sunrise and sunrise. Published and distributed privately, the book cost him some £10,000. To pay off his debt he made a popular abridgment (in two nights, with the help of two other airmen), the best-selling Revolt in the Desert. Lawrence himself never made a penny out of either book but some of his friends did. He sent a copy of Seven Pillars of Wisdom to his good, hard-up friend Poet Robert Graves, with a note, "Please sell when read." Graves sold it for £300. Offered a French translation of Revolt in the Desert, Lawrence gave his permission on one condition—that the book must have printed on its jacket: "The profits of this book will be devoted to a fund for the victims of French cruelty in Syria." Present U. S. price of a copy of Seven Pillars of Wisdom: $1,000 (alltime highest price: $5,000).

The Man. Born 44 years ago at Tremadoc, Wales of a good but not famed family with mixed Irish, Hebridean, Spanish and Norse blood, Thomas Edward Lawrence was one of five sons. His childhood was spent in Scotland, the Isle of Man, Jersey, France. Hampshire. His family moved to Oxford and he went to school there. At 13 he began a series of solo bicycle tours, made a large collection of brass-rubbings from old monuments in country churches. At 16 he broke a leg wrestling with another boy at school. He said nothing about it, rode home at the end of the day on a bicycle. He has never grown since. (He is 5 ft. 5½ in.) He took no interest in sports "because they were organized, because they had rules, because they had results." When he won a scholarship at Jesus College (partial to the Welsh) he lived at home except for one term, read voraciously, often 18 hours a day, learned how to get the gist out of any book in half an hour. Unprepared for his finals, he was advised to submit a special supplementary thesis, and went to Syria to study the Crusaders' castles there—alone, on foot, in European dress. He came back four months later with sketch-plans and photographs of every medieval fortress in Syria. His thesis won him a First Class Honours degree.

At the start of the War, Lawrence tried to join an O. T. C. at Oxford, was turned down because there were too many recruits. He got a temporary job in the Geographic Section of the General Staff. Four months later he was sent to Egypt. There, besides making himself a thorn in the flesh of red-taped, uninformed superiors, he did such jobs as edit a handbook of information about the Turkish Army, containing such unsoldierly comments as "General Abd el Mahmoud commanding the —th Division is half-Albanian by birth and a consumptive; an able officer and a gunnery expert; but a vicious scoundrel, and will accept bribes." Chafing at the restrictions and routine of army life in Cairo. Lawrence cast an envious eye at the Arab revolt just getting under way across the Red Sea. He made a general nuisance of himself till he got ten days' leave. He headed straight for Feisal's army, was received by Feisal with the question: "And do you like our place here in Wadi Safra?" Said Lawrence: "Well; but it is far from Damascus." The story of the Arab revolt and Lawrence's part in it is now history. He and Feisal took to each other immediately; so did he and Auda, sheik of the Abu Tayi Howeitat, most famed fighter in Arabia, who had killed 75 men in battle, "not counting Turks." First merely a liaison officer, Lawrence's powers increased with his achievements until at the end of the War he was practically directing the Arab irregulars who helped General Allenby roll the Turks out of Palestine. Before the War was over the Turkish reward for Lawrence, dead or alive, was £10,000. With the Arabs masters of their goal, Damascus, Lawrence quietly faded out of the picture.

At the Peace Conference Lawrence was a member of the British Delegation and acted as Feisal's interpreter; fought hard to help the Arabs keep what they had won. When Syria was made a French mandate and Mesopotamia British, Lawrence refused to accept any British decorations, feeling that the part he had played in the Arab revolt was dishonorable both to himself and to his country. Recommended for the C. B. and D. S. O. and called to Buckingham Palace by the King, Lawrence explained his position, said afterwards, "The King was most kind and understanding." The French Croix de Guerre which he had already received in Arabia he had left behind in a chocolate box. (Lawrence declared himself satisfied with Winston Churchill's later settlement of the Middle East—in which Lawrence helped—by which Feisal was made King of Irak and Great Britain entered into treaty relations with Irak.) Demobilized, Lawrence took up his residence as a Fellow of All Souls. But the academic life sat ill upon him.

In 1922 Lawrence enlisted as a private in the Royal Air Force, under the name of Ross. At the first inspection, the Wing-Commander noticed some unusual books in Lawrence's locker, asked: "Do you read that sort of thing? What were you in civil life?"

"Nothing special, sir."

"Why did you join the Air Force?"

"I think I must have had a mental breakdown, sir."

Next day Lawrence got off by explaining that the Wing-Commander had misunderstood him. Soon forced to leave the R. A. F. because the Secretary of State for Air "feared that questions might be asked in the House of Commons as to what he was doing there under an assumed name," he got official permission to enlist in the Tank Corps instead. Two years later he was allowed to transfer back to the R. A. F., was sent overseas to the Indian frontier. But Lawrence had become such a legend in the Near East that rumors kept cropping up that he had been seen here, there, everywhere on some mysterious, fateful errand. In 1928 he was transferred back to England, is now at Mountbatten, R. A. F. station near Plymouth.

There, steadfastly refusing all promotion, living in an army hut with 19 other men, Aircraftsman Shaw tinkers his engines, sweeps floors, takes his turn at all fatigues, says "Sir" to his inferiors. Spare hours he spends driving his U. S.-built speedboat 40 knots, or booming across hilly Salisbury Plain on his racing Brough-Superior motor-bicycle. Every year he is given a new model by the makers, repays them by making and reporting stiff tests. Though he has no interest in women as such, his great & good friend Lady Astor has been known to ride pillion behind him. Gas for his motorbike and speedboat, as also records for his large collection of "tinned music," he buys out of his meagre pay. Long-faced, long-chinned, long waisted, Aircraftsman Shaw looks bright but not commanding. Robert Graves describes him: "He has a trick of holding his hands loosely folded below his breast, the elbows to his sides, and carries his head a little tilted, the eyes on the ground. He can sit or stand for hours at a stretch without moving a muscle. He talks in short sentences, deliberately and quietly without accenting his words strongly. He grins a lot and laughs seldom. He is a dead shot with a pistol and a good rifle-shot. His greatest natural gift is being able to switch off the current of his personality whenever he wishes to be unnoticed in company. He can look heavy and stupid, even vulgar; and uses this power constantly in self-protection. . . . He is uncomfortable with strangers: this is what is called his shyness. . . . He avoids eating with other people. ... He hates waiting more than two minutes for a meal or spending more than five minutes on a meal." He eats anything from diseased camel meat up. Says he, "To me, all food is alike except oysters and parsley. I don't like oysters. I'm not fond of parsley—tastes like a grave." He "avoids regular hours of sleep. . . . Perhaps his most unexpected personal characteristic is that he never looks at a man's face and never recognizes a face. ... He can be relentless to the point of cruelty: the shock of his anger, which is a cold, quiet, laughing anger, is violent. ... He does not believe that heroes exist or ever have existed; he suspects them all of being frauds ... an incurable romantic . . . obvious menace to civilization."

Shaw's ambitions are two: to become a writer on his own merits (he has tried in vain to get his work accepted under a pseudonym); to make a parachute jump ("and I don't care what the result is either"). His enlistment expires on March 11, 1935. Then he may either re-enlist or settle in his Somerset cottage and write for a living—£4 a week, in his opinion; "far too much trouble to work for more."

Once, for a pal in the R. A. F., Shaw filled in this personal report: "Favorite color: scarlet. Favorite dish: bread & water. Favorite musician: Mozart. Favorite author: Wm. Morris. Favorite character in history: Nil. Favorite place: London. Greatest pleasure: sleep. Greatest pain: noise. Greatest fear: animal spirits. Greatest wish: to be forgotten of my friends."

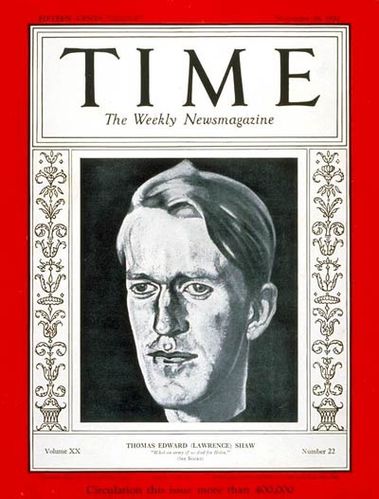

Voici la couverture de ce magazine:

A bientôt, ici ou ailleurs.

See you soon happy taxpayers !

-Denis-